The Algebraist

Rough drafts are fresh powder for the imagination. Discovering what comes next in a story as you write it. Constantly seeking to subvert your expectations for the work. Collecting dots and then finding surprising ways to connect them. Fanning the fragile spark of an idea into the roaring bonfire of a finale.

I took an improv class in college, and, for me, writing the rough draft of a novel feels a lot like getting up in front of a live audience without a script and creating a shared experience from the only raw material any of us ever has access to: here, now.

Revision is where I struggle. Instead of the infinite possibilities of a blank page, I have to confront the flaws and limitations of a manuscript. It’s not about making something from nothing. It’s about taking something and making it better. Any change you make ripples out through the story, requiring more changes that ripple out through the story, requiring yet more changes that ripple out through the story, etc.—work begetting even more work. I often feel like I’m not making progress, or even going backward. I dream of the new rough draft I could be writing instead. I second guess potential improvements because of how much time they’d take to implement, I second guess potential improvements because I worry they might backfire and ruin the good parts, and then I second guess my second guesses. Sometimes I want to trash the whole project. Revision is exhausting and frustrating and demoralizing.

But by far the worst thing about revision is this: it works.

If you’ve read one of my novels, rest assured that it’s way better than the rough draft—a caterpillar to butterfly transformation. It might be fleshing out the spare bits, or trimming unnecessary sections, or noticing an opportunity for a revelatory twist, or pushing an idea further, or deepening a relationship with a particular character, or patching a gaping hole, or doubling down on something that’s working, or shuffling cause and effect, or a thousand other things. I wish it didn’t, but struggling to make a story better really does make the story better. Often, I don’t figure out what a novel is really about until I revise it.

By now, you may have guessed that I am in the middle of revising a new novel. And I think it’s time for me to revise what revision means to me. Gardeners must weed, but they can choose whether to focus on how annoying it is to uproot the thistle or how wonderful it is to create space for their cherished flowers to thrive. I’m making a new choice—to iterate toward beauty, to struggle in service of crafting the best story I possibly can, to relish revision.

So please excuse me, I have a manuscript to get back to…

And now, a book I love that you might too:

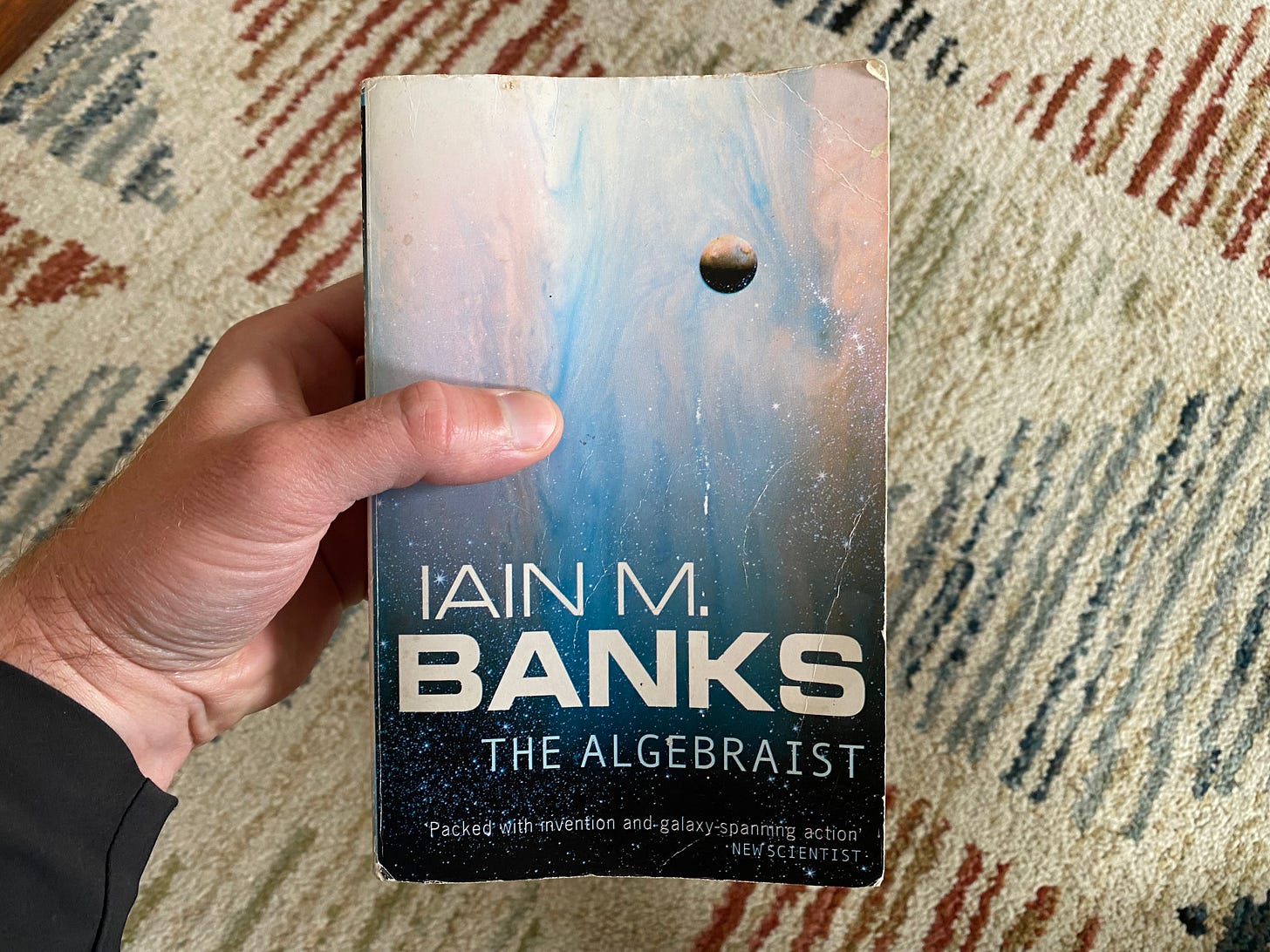

The Algebraist by Iain M. Banks takes you on an epic adventure through a far-future galaxy teeming with advanced extraterrestrial civilizations (the only reason we haven’t already noticed them in our parochial present is because we haven’t yet developed sufficiently sophisticated technology to observe or interact with them). The story follows a human anthropologist-ambassador whose vocation requires cultivating relationships with an alien species whose individuals live for billions of years. As intrigue escalates to open war, the novel explores the profound implications of this extraordinary gap in time horizons. How would we see the world and treat each other differently if we could outlive stars?

Things worth sharing:

Bandwidth just hit 2,000 Amazon reviews. Thanks! You are the best readers any writer could hope for.

From my work-in-progress: “There were still enough holes in the story to give an editor an aneurism, but this wasn’t journalism, this was espionage, and the stories spooks care about consist almost entirely of holes.”

Like everyone else on the internet, I’ve been playing with GPT-4. Because they’re trained on written culture, language models operate according to narrative rules just like reality operates according to the laws of physics. In a thought-provoking essay,

explains why story is integral to making sense of and making the most of AI.The Possibility Engine: “The moment we pass a law, adopt a puppy, discover a new scientific principle, publish a blog post, solve a problem, start a business, or ask someone on a date, it forms the context for the next moment. We stand in the present, forging the past.”

Don't assume that systems you're appraising from the outside work any better than systems you've seen from the inside.

Andy Sparks shared a favorite quote from Bandwidth: “Building something meaningful requires you to let go of the obsession with perfection. It requires empowering others and trusting them to do their part, even if they do it differently than you might have. But trust is a two-way street. Autonomy means you're held accountable.”

Good stories have beginnings, middles, and ends. With the abundance of cancelled series, Netflix et al ignore narrative closure at their own risk: we won’t trust them enough to watch new, unfinished shows.

Wondering how Neon Fever Dream earned its title? See this mind-boggling photo.

It’s amazing how much you can accomplish when you do one thing at a time.

Thanks for reading. We all find our next favorite book because someone we trust recommends it. So when you fall in love with a story, tell your friends. Culture is a collective project in which we all have a stake and a voice.

Best, Eliot

Eliot Peper is the author of Reap3r, Veil, Breach, Borderless, Bandwidth, Neon Fever Dream, Cumulus, Exit Strategy, Power Play, and Version 1.0. He also works on special projects crafting stories to inform, entertain, and inspire.

“This is the best kind of science fiction, in which the overriding issue of our time, climate change, is addressed with vivid characters serving as exemplars of all the roles we need to take on in the coming decades, all gnarled into a breathtaking plot. I hope it’s the first of many such novels creating climate fiction for our time.”

-Kim Stanley Robinson, author of The Ministry for the Future, on Veil