Solving weirdly specific problems

When I’m not writing novels, I’m often surfing. A good wave requires the confluence of the right swell, wind, and tide for a given spot, so serious surfers invariably become amateur meteorologists.

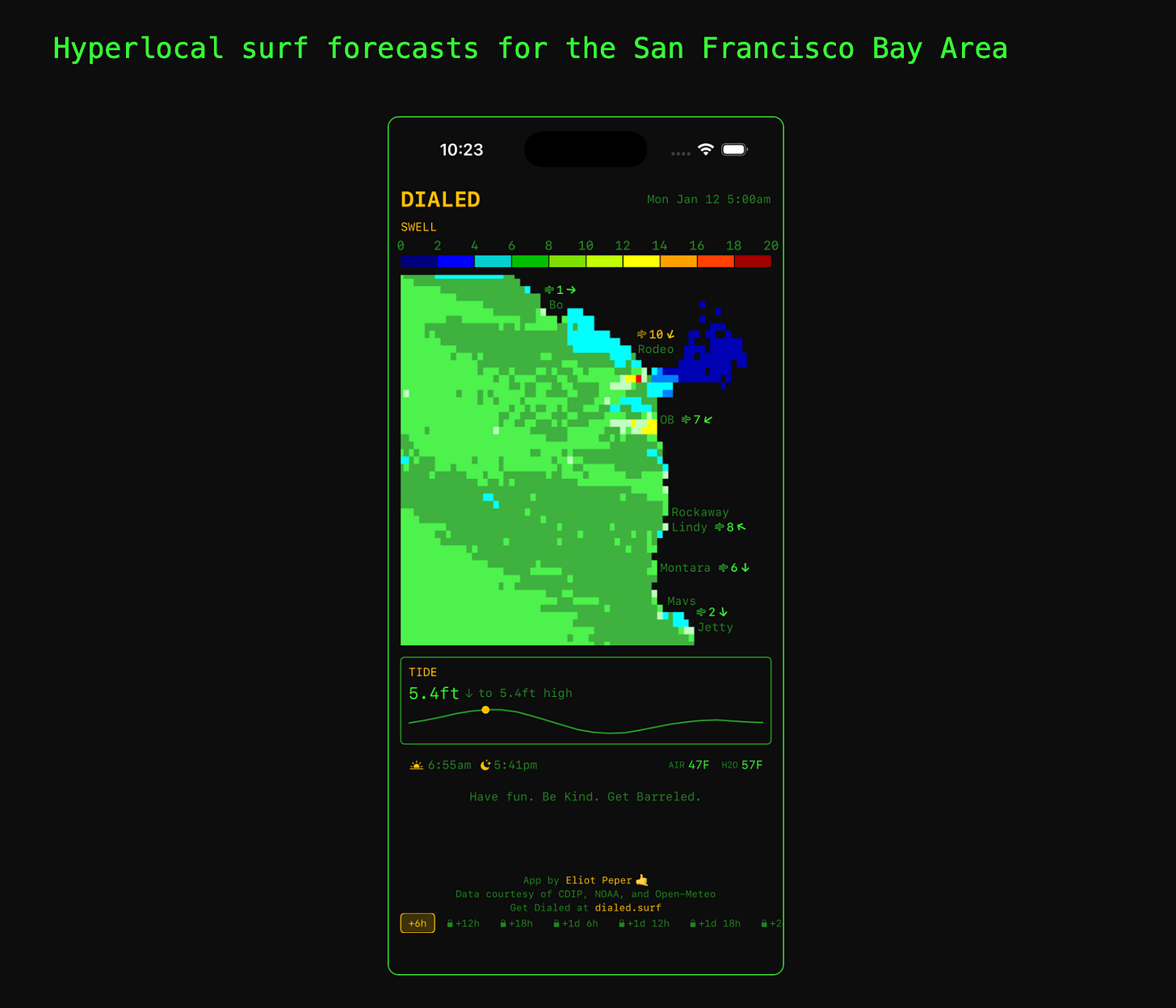

For years, a company called Surfline has enjoyed a comfortable global monopoly in surf forecasting, but their predictions are infamously unreliable for San Francisco’s powerful, shifty beach breaks. So, like many other Bay Area surfers, I check obscure websites that post raw oceanographic data to get a sense of what to expect.

When my friend Andrew showed me his homemade astronomy app, I was inspired to see if I could build myself a hyperlocal surf forecasting app fine-tuned for the Bay Area.

With approximately zero programming experience, I spun up Claude Code for the first time, identified the best public data sources, defined exactly what I wanted, created a detailed plan, and pressed go, conjuring a ghostly legion of tireless minds to weave this idea into reality.

Claude and its minions built the entire working app in a single shot.

I was delighted! So I iterated the design, added a bunch of features, and started using it daily.

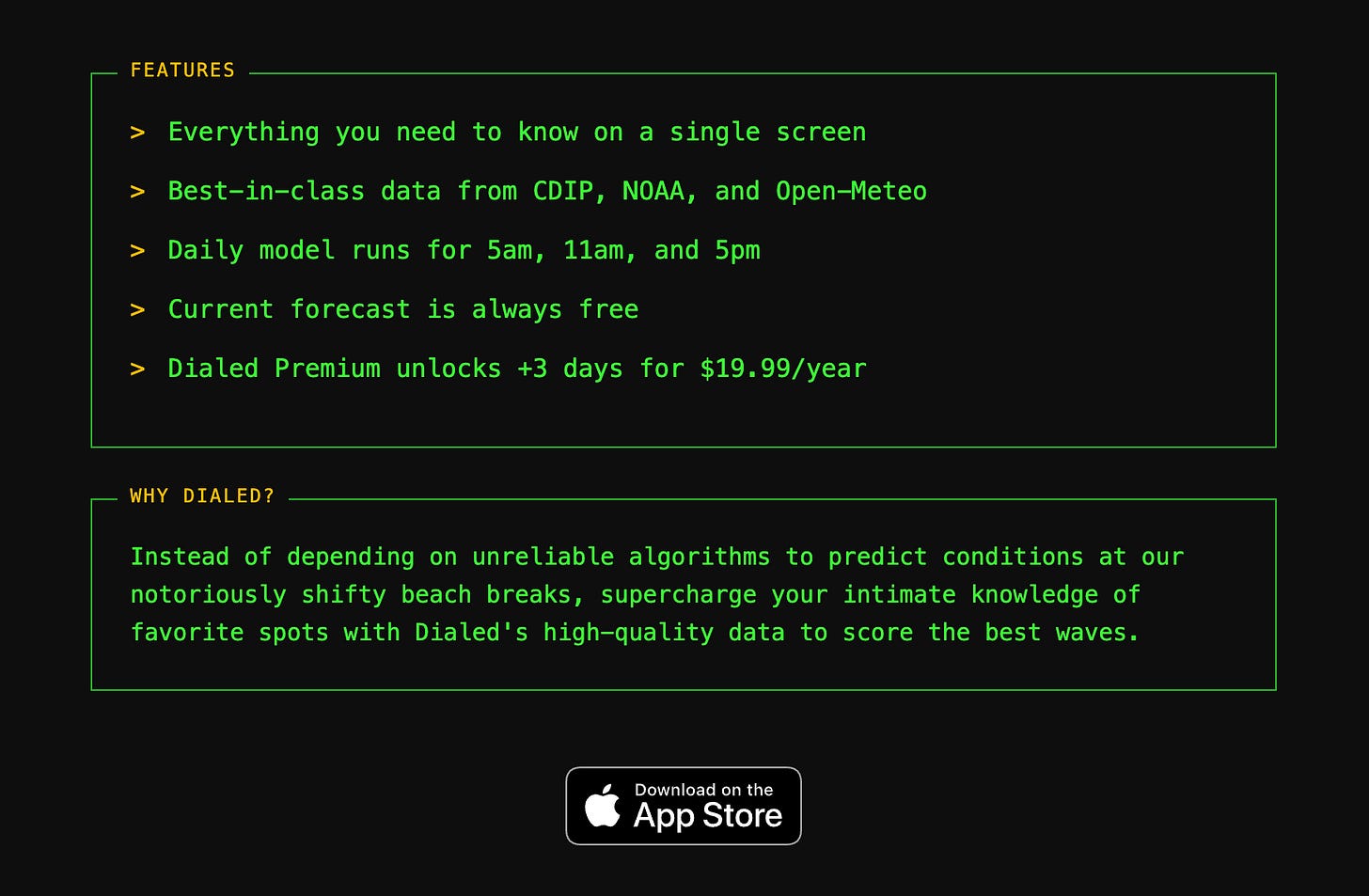

Then friends asked to use it, which meant I needed to get it in the App Store. And if I was going to do that, I should add a modest paid subscription to support maintaining and improving it over time. And obviously I'd need a landing page, so I worked with Claude to build and deploy the site.

I honestly can’t quite believe it myself, but Dialed just launched in the app store.

Dialed is extremely simple. All it does is bring data from different public sources into one place to help you decide when and where to surf along this beautiful stretch of coastline.

With its global scale, it would never make sense for Surfline to do something this niche, nor would the teeny, tiny addressable market for Dialed justify the time or investment required to build it without AI tools. But with those tools, I was able to create a piece of software to solve my own weirdly specific problem, and offer it to others who might find it useful.

What other weirdly specific problems have abruptly become feasible to solve?

A book I love that you might too

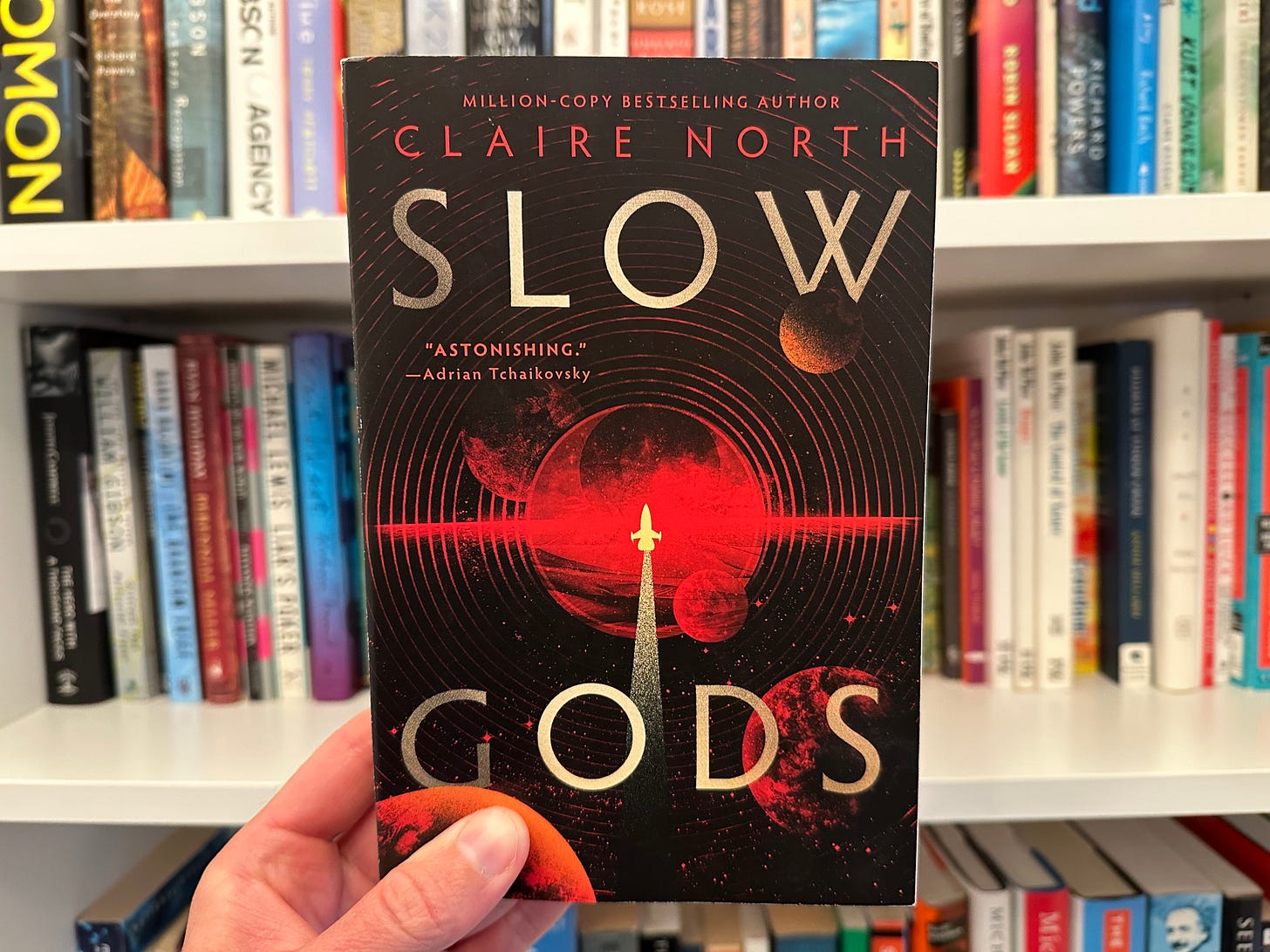

Slow Gods by Claire North is the best science-fiction novel I’ve read in a good while. Buzzing with strange and beautiful ideas, the story moves between scales with uncommon fluency, zooming in on intimate moments charged with personal meaning and spiraling out to show how the consequences of the choices made in those moments ripple out through time, space, and history. Stars collide. Cultures clash. Planets die. New worlds, new friendships, and new gods, are born. This is an adventure worth embarking on.

Instead of focusing on explicit goals, do the next most interesting thing

They argued that when an individual, organization, or complex AI system is attempting to accomplish a large and difficult goal, explicitly aiming toward that goal can often be counterproductive. In essence, their argument is that in a complex space of possibilities, aiming directly for some objective leads to cul-de-sacs or unfruitful directions. For example, if you are the inscrutable process of evolution and want to evolve flying birds, you might first want to create feathers, a seemingly unrelated development evolved perhaps for temperature control. But then these feathers get co-opted for the entirely unexpected purpose of flight. So, too, in technology and innovation. Stanley and Lehman examine how vacuum tubes—an essential component of early digital computers-were not invented for this purpose at all. But once in hand, they could be used by computing pioneers to build those large machines.

Stanley and Lehman write of the importance of focusing one’s quest on novelty and interestingness. When new capabilities are developed-what they call stepping stones-they can be productively combined in exciting ways and used to traverse the deep waters of innovation, slowly making one’s way toward the eventual goal.

From Samuel Arbesman’s The Magic of Code.

7 links worth tapping

OpenAI published a case study on how we engineer Tolan personality.

The TechStuff podcast interviewed me about how science fiction changes the real world.

Robin Sloan launched a new pop-up newsletter. Instant subscribe.

Ben Springwater just rebooted his wonderful publication Words That Matter in which writers curate their favorite reads on the internet (here are my picks).

Despite everything, people still read books

The internet may have disrupted newspapers, magazines, music, and Hollywood, and yet it’s 2026 and book sales continue to slowly, steadily grow.

In the words of the one and only Douglas Adams, “Look at a book. A book is the right size to be a book. They’re solar-powered. If you drop them, they keep on being a book. You can find your place in microseconds. Books are really good at being books and no matter what happens books will survive.”

Thanks for reading

We all find our next favorite book because someone we trust recommends it. So when you fall in love with a story, tell your friends. Culture is a collective project in which we all have a stake and a voice.

Best, Eliot

Eliot Peper is the author of twelve novels, including Foundry, Bandwidth, Cumulus, and, most recently, Ensorcelled. He is also the head of story at Portola and works on special projects.

“Real and urgent. I read it all in a single fascinated sitting.”

-The New York Times Book Review on Bandwidth