Sometimes a book starts slow but eventually seduces you. Sometimes a book opens hot and fast but eventually loses you. And sometimes, when you’re very lucky, a book clicks with you from the very first sentence and then deepens that sense of connection with every page.

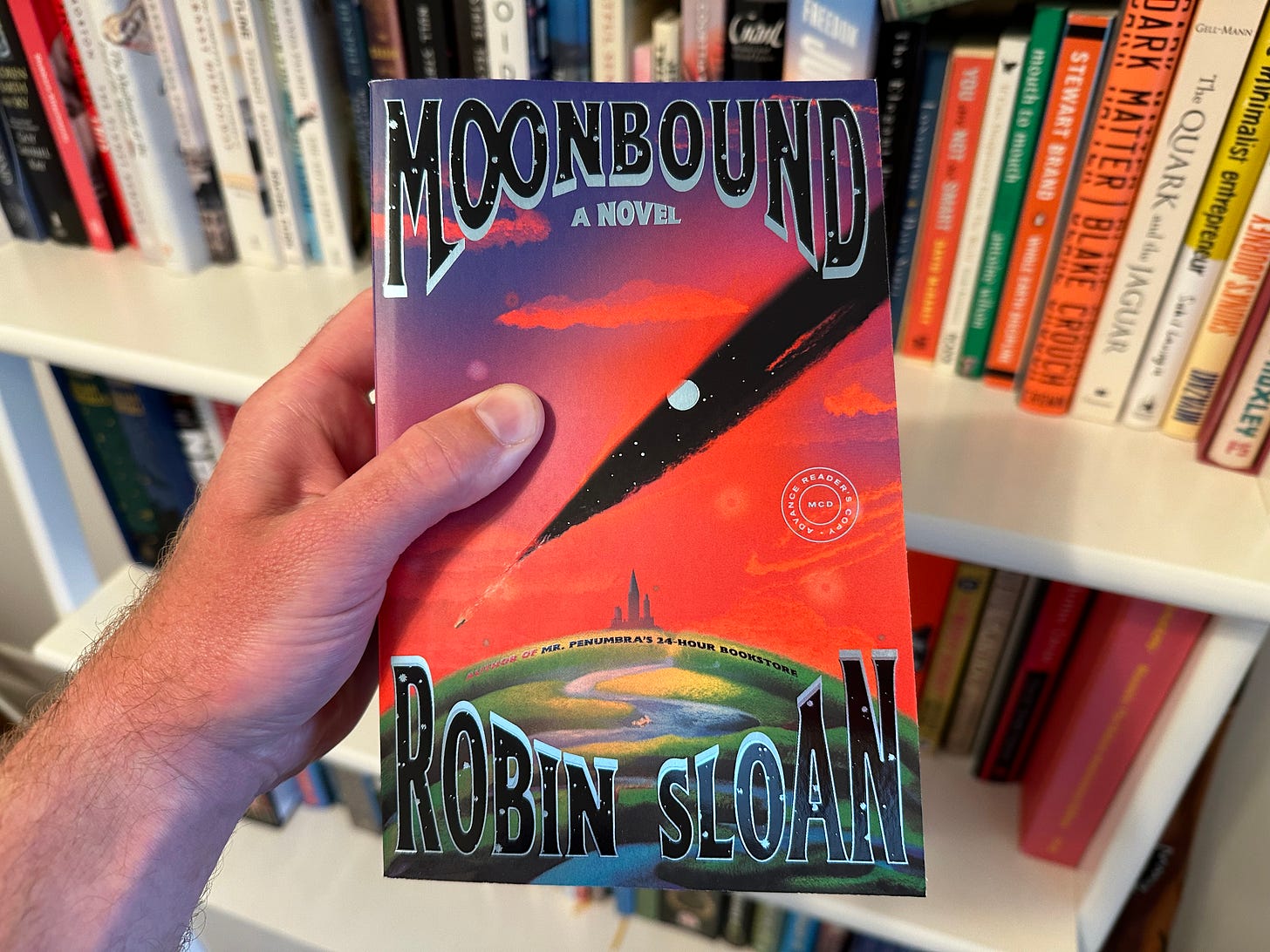

That’s how Moonbound made me feel—here’s how I described it in a previous post:

Moonbound by Robin Sloan is a wildly imaginative adventure that will pique your curiosity, subvert your expectations, and stoke your desire to find out what happens next. There are dragons made of code. There are wizards who engineer genes. Scholars swim in pools of high-dimensional math and beavers construct intricate arguments out of woven reeds. There is a boy. There is a sword in a stone. None of these things are quite what you think they are, and discovering the manifold hidden connections is tremendous fun. There’s nothing quite like a good story well told. Moonbound is one of those. I wish I could read it again for the first time.

I’ve been anticipating this book for a long time, since long before it was first announced. Every few months, Robin, Hannu Rajaniemi, and I get lunch and chat about writing novels and things that are interesting to novelists: what we’re struggling with in our respective projects, the weird and wonderful and maddening world of publishing, forgotten but alluring subgenres like 19th century adventure fiction, and leveraging new mRNA technology to build immune-computer interfaces (that’s mostly Hannu!).

Over time, I realized that Robin is more than a great writer, he’s also great at talking about what he’s writing. Whoever you are, whatever you do, there’s the work, and then there’s the work around the work: bringing your thing to the right people in the right way, finding ways to spark curiosity and cultivate solidarity, weaving a new thread into our evolving culture.

I wanted to find a way to share a taste of those writerly conversations with you. So to celebrate Moonbound’s release (today!), I interviewed Robin about why and how he wrote it.

Enjoy, and let me know what you think.

My sources whisper that Moonbound was born on a desert odyssey. What is this story’s origin story?

By the tail end of 2020, I'd been thinking about this book for many years and, naturally, had not drafted a single line. This was, and is, a bit unusual for me; normally I can produce a first draft without too much drama. But I was so attached to this idea, to the possibility I sensed, that I was afraid of "ruining it" with actual prose.

Drastic measures were required. In early 2021, I drove to a rented cabin in Joshua Tree with two sacks full of groceries. My objective was simple: come back with text. I did—four or five chapters' worth, not a huge amount, all totally cruddy, but the important thing was, the work had officially begun.

Why are hand-drawn maps so integral to fantasy novels? What role did geography play in imagining Moonbound?

Maps are most at home in fantasy novels, but they're used across genres, and in a sense, they define my favorite genre of all: "books with a map on the first page"! I think it's simple, really. Maps are the vista: "I can see it, but I haven't been there yet." That's such a human thing. Deeply enticing, on an almost cellular level.

I should say, though, that Moonbound takes place on our real planet, not some imaginary counter-world, a Narnia or a Westeros. Yet, I didn't want to simply print a familiar map of the world on the first page… boring! Solving this aesthetic puzzle was fun, and, as you know, the solution is revealed over the course of the book.

Please introduce us to the fundamentals of Gibson-Faulkner Theory.

Ah! Thank you for asking (and, to your readers, I'm sorry). G-F Theory is, of course, the great policy planning framework of the Anth, which is what I call human civilization at its apex—our near future. The idea is that it's a system for imagining and executing big projects that actually works. The theory emerges from the intersection of two maxims.

First, there's William Gibson: "The future is already here—it's just not evenly distributed."

Then, there's William Faulkner: "The past is never dead. It's not even past."

Mashing those together, we get an interesting view of the present, not as a point on a continuum, but rather a smear, a bleed, a diffusion of events and possibilities. (It's well-known that early Gibson-Faulkner theorists were also influenced by Alan Jacobs and his concept of "temporal bandwidth".)

I elucidate G-F Theory a bit more in the book, and also in some accompanying zines, but readers can imagine it as a kind of super-economics, a quantitative social science that takes the richness of the past and the future seriously, understands that they vibrate against each other in complex ways. "Psychohistory lite"? Sure!

Why is the choice of scale so important? What can you learn at the scale of a journey that you can’t from an overview, and vice versa? How did you play with scale in the writing of Moonbound? What are the particular affordances of operating at the scale of a novel?

That's a big question! Or maybe I should say—an interesting choice of scale for a question. For me, scale is a primary attraction of science fiction, as a genre. Of course, there's plenty of sci-fi that plays out in the near future, or even the present; and in the space of a neighborhood, or even a family. But my favorite examples of the genre go big. I love the science fiction of Iain M. Banks and Adrian Tchaikovsky, of Isaac Asimov and Ann Leckie.

However, I acknowledge the risk of scale, which is always: numbness. That's why dynamic range is important. Going big works better when you start small—when you zoom out step by step. Interestingly, I think video games, of all media, tend to do this best. Very often, you begin in darkness, on a little island of pixels. By the game's conclusion, whether it's an RPG or a civilization sim, you've opened up a vast world. It's thrilling! And I am bent on capturing some of that thrill for myself.

Moonbound is the first piece of science fiction I’ve encountered that genuinely engages with the potential and risks of current advances in AI (without ever needing to explicitly say so). What common misunderstandings of AI are you attempting to subvert, and what surprising possibilities are you excited to riff on? What are the most important distinctions between human, (other) animal, and machine intelligence, and what unexpected aspects of intelligence do we have in common?

Well, it's an interesting twist—and I do think it's just that: a twist of fate; a roll of the dice—that the AI systems that have leapt into the world so prominently are, of all things, language models. This has at least two interesting implications:

1. Their training data is language, which is to say, it's partially literary. As you know, this has consequences in Moonbound's story, which I won't spoil here. But suffice it to say, in our world as much as Moonbound's, it grants a special position, at least for the moment, to the people who produced all that language.

2. The models are understandable, at least in part, as literary artifacts! It's as if engineers gave language itself the ability to stand up and speak. To be interrogated. Which language? Whose language? Exactly! I feel like a huge bag of fascinating questions just dropped out of the sky, and they are questions not only (or even primarily) for computer scientists but also for poets and philosophers. Get on it, people!

What is high-dimensional thinking and how might one apply it to, say, making olive oil?

I'm not sure there is a kind of thinking that ISN'T high-dimensional. Here's what I mean by that:

The aforementioned AI language models—indeed, many kinds of AI systems—operate by projecting their inputs and outputs into a high-dimensional space: a coordinate system with thousands of axes, rather than the familiar three of real space, or even the meager four of spacetime (and much sci-fi).

Humans simply CANNOT visualize these spaces—even the greats admit that—but we can do math in them, and we can write computer programs that access them.

It turns out some really interesting things happen in these spaces when AI systems learn to "embed" training data in them. The coordinate for the word "king" (thousands of numbers long) finds itself fairly close to the coordinate for "queen"; moreover, the direction BETWEEN "king" and "queen" (and what is a "direction" in high-dimensional space? Don't try to visualize it!!) is the same, exactly, as the direction between "man" and "woman". Analogies become spatial, when the space is rich enough.

This is all a super simplistic way of saying, there seems to be a way to arrange complex information very meaningfully inside these high-dimensional spaces, and then navigate around it—translating, rotating, hopping, slinking—in ways that are surprising and sometimes useful.

Now, this is conjecture, but I think there is probably a high-dimensional space inside our own minds, represented somehow in the substrate of physical neurons. How many dimensions? I don't know. How does it work? I definitely don't know. I can only report that, learning about high-dimensional spaces in AI systems, exploring them, I have felt powerful twinges of recognition and resonance.

Anyway, that's all to say, making olive oil is high-dimensional like everything else!

All your books weave in speculative elements, but Moonbound is your first “straightforwardly sci-fi” novel. As a writer and a reader, how do you think about genre? What role does science fiction play in the larger culture?

Yeah, I don't think the choice is "genre or not" but always, "which genre?" Sci-fi is a genre, and fantasy is a genre, and so is literary fiction, of course. Someone called my first novel, Mr. Penumbra's 24-Hour Bookstore, a work of "puzzle fiction": not quite a mystery, not quite literary fiction, or maybe both at once—a hybrid. I like that. Genre at its best isn't a rigid filter; rather, it's a map, a family tree. A network of debts and influences.

Moonbound is dense with nods and winks, homage and allusion, and most of that is directed toward either (1) science fiction, or (2) fantasy in the register of C. S. Lewis or Ursula K. Le Guin or even Hayao Miyazaki. There you have it!

What does “planetary writing” mean, and why is it important?

I don't know if he coined the term, but I found "planetary writing" through J. M. Ledgard, specifically in the context of his terrific novel Submergence. He said:

So there is on the surface a narrative where human lives are played out and they matter so very much and are insignificant all at once. Whereas the ocean is confounding in another way, you have no breath in it, no light, and consequently no imaginable human life, yet it is immutable, and when you stack it up you find it is nearly all of the living space on the planet. What I wanted to do was to alter the reader’s perspective of Earth, to show that dirt is precious but seawater dominates, to step out on a field is rare while to float and scintillate with bioluminescence is common.

For me, "planetary writing" is simply about taking the planet—and by extension the universe—seriously. It means cultivating and pursuing deep curiosity about Earth's real processes, rather than accepting the anthropomorphic cartoon versions. I mean, this is why I downloaded the far-future ephemeris from NASA, with the tracks they've calculated for the planets in the year 13777, which is when Moonbound takes place. I wanted Jupiter's position in the sky, on the page, to be its real position in space, or at least modern science's best guess. Does that matter to the story? Eh, maybe not. But it matters to me. Again, it's just about taking the real world seriously.

You reformatted your long-running newsletter around Moonbound, built a companion website to support the novel, and printed and distributed a limited-edition zine for folks who preordered the novel. What is your strategy for reaching/building an audience and selling books in 2024, and what advice do you have for artists seeking to help the right people discover their work?

I do believe that an email newsletter is currently the best tool in just about any artist's arsenal. That doesn't mean it's a particularly good tool—just that all the others are presently degraded and unreliable.

The thing about the big algorithmic platforms—YouTube, TikTok, Instagram, you name it—is that you have to play their game to find an audience. If you do that, the rewards can be profound… I mean, where else, WHEN else, in the history of all media, have you been able to go from nothing to millions of viewers so quickly? But, remember: you're playing their game. You've met them halfway, or more. Ninety-two percent of the way. And I personally do not think too much original, personal art survives that encounter.

I recommend Simon Carless's GameDiscoverCo newsletter to everyone contending with these questions, even those who don't really care about video games. His deep, rigorous engagement with the reality of that marketplace, on behalf of people trying to produce actually interesting work, is almost unique in the media landscape. I wish there was a BookDiscoverCo newsletter!

What are three books you love and heartily recommend?

Knowing a bit about the Peper-verse, I have to recommend Ray Nayler's The Mountain and the Sea. It's 100% a work of planetary fiction, which we discussed earlier.

You know, along those same lines, let me recommend Reaktion's huge series of pocket-sized animal books. Taking the real world seriously doesn't have to mean contending with academic doorstops. These books are punchy, pocket-sized, packed with illustrations—yet super serious. Daniel Heath Justice's Badger was a revelation. I also appreciate the meta story here, of a cool, ongoing publishing project that's both intellectually delightful and, apparently, commercially successful.

Last one… hmm, what to choose… well, listen: surely there are some folks reading this interview who haven't yet found their way to A Wizard of Earthsea, by Ursula K. Le Guin. Here's an example of a book that was never a best seller, but/and has also, since its publication in 1968, never been out of print. Its sequels each expand and "correct" the story in fascinating ways. Basically, I think A Wizard of Earthsea is a perfect book, not in and of itself—Le Guin would tell you, she'd insist, it has problems—but as part of a larger system, and as evidence of what books, at their best, can do.

Eliot Peper is the author of Foundry, Reap3r, Veil, Breach, Borderless, Bandwidth, Neon Fever Dream, Cumulus, Exit Strategy, Power Play, and Version 1.0. He also consults on special projects.

“A precision engineered labyrinth of spies and semiconductors.”

-Hannu Rajaniemi, author of The Quantum Thief, on Foundry

Sadly not a kindle yet :-(